Axions

The axion is a hypothetical type of particle that was proposed in the 1970s as a solution to the strong CP problem in particle physics. The strong CP problem refers to the fact that the strong nuclear force appears to conserve the symmetry of charge and parity (CP), which could be violated according to the standard model of particle physics.

The axion was proposed as a new particle that would solve this problem by introducing a new symmetry called the Peccei-Quinn symmetry. This symmetry would ensure that the strong nuclear force conserves CP symmetry and would also give rise to a new particle, the axion, which would be very light and weakly interacting.

Because the axion is weakly interacting, it would be difficult to detect directly. However, in certain mass (ultra-light, see below) and coupling regimes axions could still have significant effects on the universe, such as influencing the large-scale structure of galaxies and contributing to the cosmic microwave background radiation.

There are ongoing efforts to detect axions either directly in experiments like ADMX or indirectly through its effects on astrophysical and cosmological phenomena, such as the observation of the cosmic microwave background by experiments like Planck and BICEP/Keck. However, so far there has been no direct detection of axions.

QCD Axions

The mass of the classic QCD axion is not known with certainty, and it is one of the key properties that experimental efforts are attempting to determine. The mass of the axion is expected to be very light, with a range of possible values from as low as 1 micro-electronvolt (μeV) to as high as several milli-electronvolts (meV).

The exact value of the axion mass depends on the details of the Peccei-Quinn (PQ) mechanism and the energy scale at which the symmetry is broken. There are also different theoretical models that predict different values of the axion mass.

Experimental searches for the QCD axion are typically designed to target a specific mass range based on theoretical predictions. For example, the Axion Dark Matter eXperiment (ADMX) is focused on searching for axions with a mass in the range of 1 to 10 μeV. Other experiments, such as the Haloscope At Yale Sensitive to Axion Cold Dark Matter (HAYSTAC), the Magnetized Disc and Mirror Axion experiment (MADMAX), the CAPP Ultra-Low Temperature Axion Search in Korea (CULTASK), and the Cosmic Axion Spin Precession Experiment (CASPEr), are searching for axions with higher masses in the (sub-)meV range.

Despite decades of effort, the mass of the axion remains an open question, and further experimental searches will be necessary to determine its properties.

The axion field after PQ symmetry breaking (post-inflation) acts as a cold dark matter (CDM) condensate, and is thus a promising CDM candidate.

Ultra-Light Axion Dark Matter

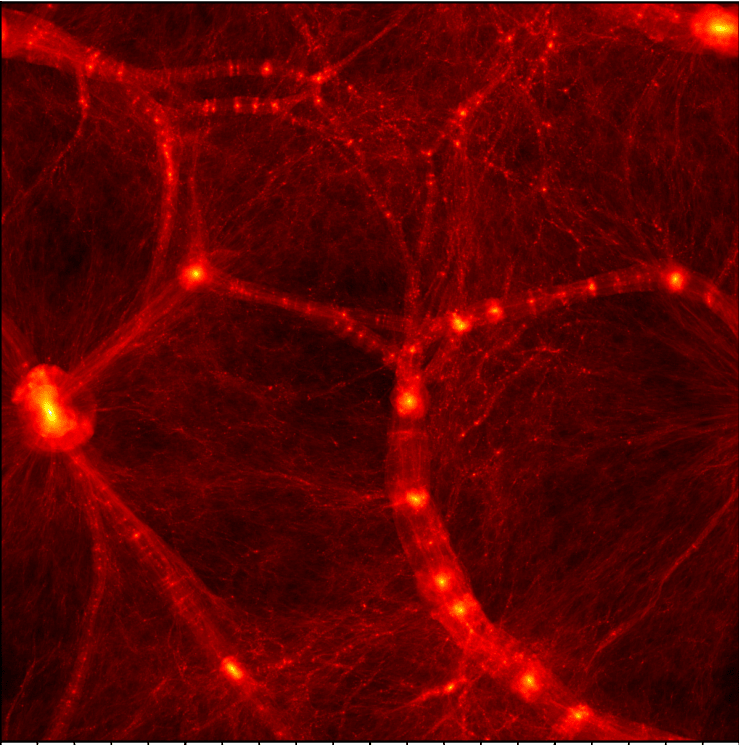

Another cold dark matter candidate are ultra-light axions (ULAs). ULAs are a class of axion particles that have masses in the range of about \(10^{-26}\) to \(10^{-16}\) eV. These axions are often referred to as “fuzzy” dark matter because their very low mass gives them a wavelength that is comparable to the size of small galaxies (kpc scales), which could lead to interesting effects on galactic structure.

One of the main motivations for studying ULAs is their potential impact on the structure of galaxies. Because their wavelength is comparable to the size of small galaxies, ULAs could exhibit wave-like behavior, forming a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) that would affect the distribution of matter in galaxies. This could potentially solve some of the outstanding problems in our understanding of galactic structure, such as the “cusp-core” problem and the “too big to fail” problem.

Search for the effects of ULAs on astrophysical phenomena has been an ongoing effort for years. Since the presence of ULAs affects the large-scale structure of galaxies, constraints can be put on the cosmological abundance of ULAs. In addition, the polarization of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) is sensitive to ULAs and is being searched for by experiments like the Polarization of Background Radiation (POLARBEAR) experiment.

Constraints

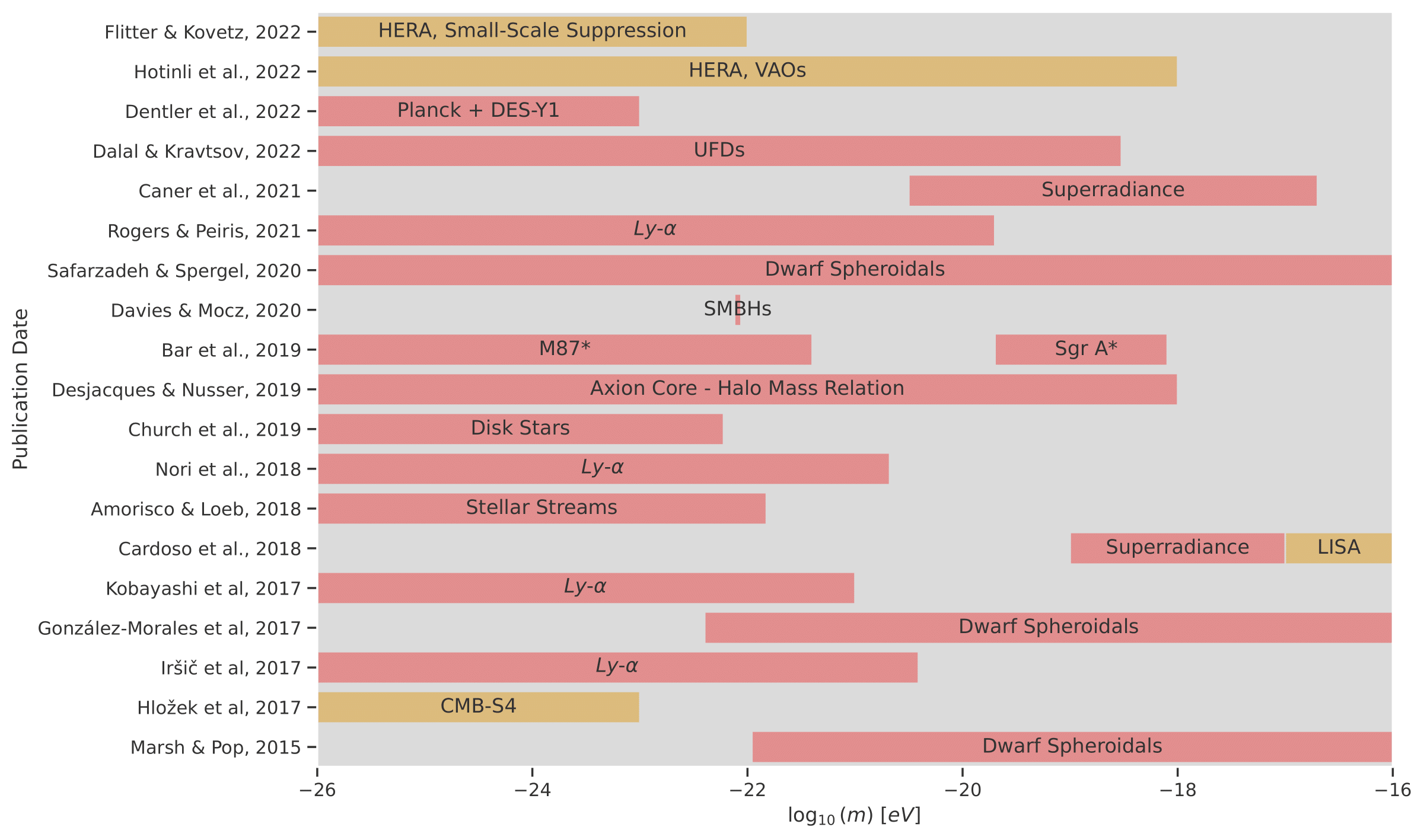

Experimental observations provide increasingly stringent bounds on the admissible mass ranges of FDM, see Dome et al 2022. In that work, we provide a non-exhaustive list of recent constraints ordered by publication date, which we also show below:

|

|---|

| Fig. 1: Recent particle mass constraints for warm dark matter (WDM) / FDM from astrophysical observations in the FDM window of \(10^{-26}\) eV \(<m<10^{-16}\) eV. The red shading indicates a disfavored parameter space, though not necessarily a \(2\sigma\)-constraint. The orange shading indicates forecasts for future observatories. UFDs = ultra-faint dwarf galaxies; SMBHs = supermassive black holes. |

While the density profiles in the central regions of dwarf spheroidals can be explained with a FDM soliton core potential provided that \(m \le 1.1 \times 10^{-22}\) eV (Marsh & Pop 2015), Ly-α observations find a lower bound \(m \ge 3.8 \times 10^{-21}\) eV to have enough power on Mpc-scales in the Ly-α forest (Irsic et al 2017), constituting a Catch-22 problem. Recently, Safarzadeh & Spergel 2020 showed that a pure FDM cosmology is inconsistent with dwarf spheroidals across the entire parameter space by at least 3σ. More sophisticated models of reionisation are needed though to make some of these observational constraints more reliable: For instance, most forest analyses assume that the frequency-averaged amplitude of the ionising background J in the neutral hydrogen density \(n_{\text{HI}} \propto (1+\delta b)^2/(T^{0.7}J)\) has negligible spatial fluctuations (Hui et al. 2017). Some FDM constraints might also be biased due to poor star formation modelling.